Party archetype pattern

Problem statement

Level 1

A large portion of software created worldwide is intended for various types of end users: individual users, employees, other applications, and systems. Therefore, there’s a good chance you've faced the challenge of building a user management system at some point. Perhaps you had to prepare a module that enables user registration, updating their information (such as first name, last name, address), authentication (including setting passwords or one-time access codes), and authorization (including defining roles).

Level 2

If the software is used to automate processes that generate revenue, the user often represents our client. Clients can be both individuals and companies. Sometimes, the client is a sole trader, combining characteristics of both an individual and a business. In some services, user registration is synonymous with client registration, though this doesn’t have to be the rule. The following scenarios, among others, are possible:

- A user registers in the system but, since they haven’t purchased a subscription (and are not technically a client), has limited access to services — in this situation, the user entity is created before (if it ever happens) an associated client entity is created.

- A client appears in the system, with whom we sign a service agreement. Only after the contract is signed might it be necessary to create one or multiple user accounts—in this situation, the user entity is created afterward.

Level 3

The problem can become even more complex when:

- a person or company is neither a user nor a client, but, for example, a lead with whom we are conducting negotiations

- a company consists of multiple departments, and we want to enable different departments to perform different operations within the system (for instance, we may have a company hierarchy in which each subsidiary can make purchases, but billing is handled solely with the parent company as the payer)

- a company that is our client can also simultaneously be our supplier/partner (e.g. a fiber optic manufacturing company orders subscription contracts with internet and phone services for its employees while also providing services as a cable supplier)

- a company with which we have signed a contract will integrate with our system via an API (i.e. there will be no user logging into our system through the UI)

What's next?

The above demonstrates that managing users, clients, partners, and various types of entities can be a very complex issue, where entities can assume multiple roles and have different relationships with each other.

Possible solutions

Let's start with a User

The evolutionary emergence of new business cases often results in an evolutionary solution design. We often see a solution that starts with a User class that manages basic user data as a person, as well as authentication and role management:

class User {

private final UserId id;

private final FirstName firstName;

private final LastName lastName;

private final EmailAddress emailAddress;

private final PasswordHash passwordHash;

private Addresses addresses;

private Roles roles;

User(UserId id, FirstName firstName, LastName lastName, EmailAddress emailAddress, Password password) {

this.id = id;

this.firstName = firstName;

this.lastName = lastName;

this.emailAddress = emailAddress;

this.passwordHash = password.hash();

this.roles = Roles.emptySet();

this.addresses = Addresses.emptySet();

}

boolean authenticate(Password password) {

return password.hash().matches(passwordHash);

}

void assign(Role role) {

roles.add(role);

}

void assignOrUpdate(Address address) {

addresses.add(address);

}

void remove(AddressId addressId) {

addresses.remove(addressId);

}

//getters if needed

//...

}

When a User can be a Customer

When a user can be a customer, a common solution is to add a boolean flag:

boolean customer;

In cases where clients are individuals (individual customers), this might be sufficient. However, if the customers are companies, issues arise, such as the fact that a company doesn’t have a first and last name but rather a business name and tax identification number, and often has various types of addresses (e.g. contact, billing). Attempting to meet these requirements within the User class would result in adding another set of data fields and address policies that would only be used in a subset of cases:

class User {

private final UserId id;

private final FirstName firstName;

private final LastName lastName;

private final CompanyName companyName;

private final TaxNumber taxNumber;

private final EmailAddress emailAddress;

private final PasswordHash passwordHash;

private Addresses addresses;

private Set<Role> roles;

//user-specific API

User(UserId id, FirstName firstName, LastName lastName, EmailAddress emailAddress, Password password) {

this.id = id;

//user data

this.firstName = firstName;

this.lastName = lastName;

this.emailAddress = emailAddress;

this.passwordHash = password.hash();

this.roles = Roles.emptySet();

this.addresses = Addresses.emptySet();

//customer data

this.companyName = null;

this.taxNumber = null;

}

boolean authenticate(Password password) {

password.hash().matches(passwordHash);

}

void assign(Role role) {

roles.add(role);

}

void assignOrUpdate(Address address) {

addresses.add(address, AddressType.RESIDENTIAL);

}

boolean isUser() {

firstName != null || lastName != null;

}

//customer-specific API

User(UserId id, CompanyName companyName, TaxNumber taxNumber, EmailAddress emailAddress) {

this.id = id;

//user data

this.firstName = null;

this.lastName = null;

this.emailAddress = emailAddress;

this.passwordHash = PasswordHash.empty();

this.roles = Roles.emptySet();

this.addresses = Addresses.emptySet();

//customer data

this.companyName = companyName;

this.taxNumber = taxNumber;

}

void assignOrUpdate(Address address, AddressType addressType) {

addresses.add(address, addressType);

}

boolean isCompany() {

companyName != null || taxNumber != null;

}

//common API

void remove(AddressId addressId) {

addresses.remove(addressId);

}

//getters if needed

//...

}

It’s evident that this model diverges from reality, where the creation of a user and a customer are often separated in time. Such a solution typically has a negative impact on the production chain, as independent streams of changes converge in a single class, increasing its complexity and reducing reusability and testability. On the client-side code, this model requires continuous checks to determine whether the object represents a user, a customer, or possibly both.

Attempting to handle additional cases (such as introducing the concept of a lead) within this model will only worsen the situation. Once again, the user and customer models often bloat due to the need to add various flags and marker fields, such as Instant agreementSignatureDate, Instant validTo, boolean active, etc. A critical requirement that challenges this model is the need to establish a one-to-many relationship between the customer and user.

What about separate models?

A solution that addresses the mentioned problems, that we often observe in such situations is the creation of use case-specific classes, namely User, Customer, and Lead. We now reach a point where each specific case requires the creation of a new specialized model. On one hand, this is beneficial because the model better reflects the forces at play in the business problem. However, when a company or individual appears in multiple forms, the solution becomes complicated again.

For example, a sole proprietorship may start as a lead, then become a client, and we set up a user account for it; afterward, the same business entity becomes our partner. As a result, we would need to duplicate the same data in the User, Customer, Lead, and Partner classes, or create classes as Cartesian products of the functionalities and data structures of each type of entity, such as CustomerPartner. In this case, solving one problem generates another.

As a result, such solutions are semantically incorrect, meaning that the model does not reflect the actual essence of the business problem, thus complicating programming on both the model and client code sides. The model is characterized by high complexity and poor functional scalability. Typically, in such situations, we observe the use of separate models by different teams, which effectively hinders data consistency, and very similar work must be done in many places by many people.

Distributed architecture

We often encounter situations where models such as User, Customer, Partner, and others are implemented across separate applications. This approach adds complexity, forcing client applications to integrate with multiple data sources. Maintaining consistency between these applications is both challenging and costly, typically having a negative impact on the delivery and operational performance. Introducing new features often requires changes across multiple applications managed by different teams. Additionally, issues with data consistency can result in customer-reported bugs needing to be analyzed and resolved by several development teams simultaneously.

Solution

The essence of the problem lies in the role-centric model. Both the attempt to enrich the User type with data and functions specific to a given role, as well as the creation of types corresponding to roles, such as Lead, Customer or Partner, cause many problems. What if the center of the model is not a role, but an entity such as a person or an organization?

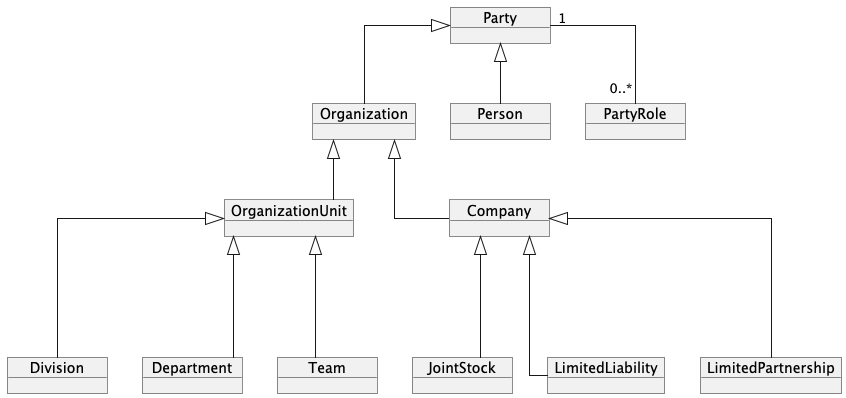

Then we get a structure similar to this one:

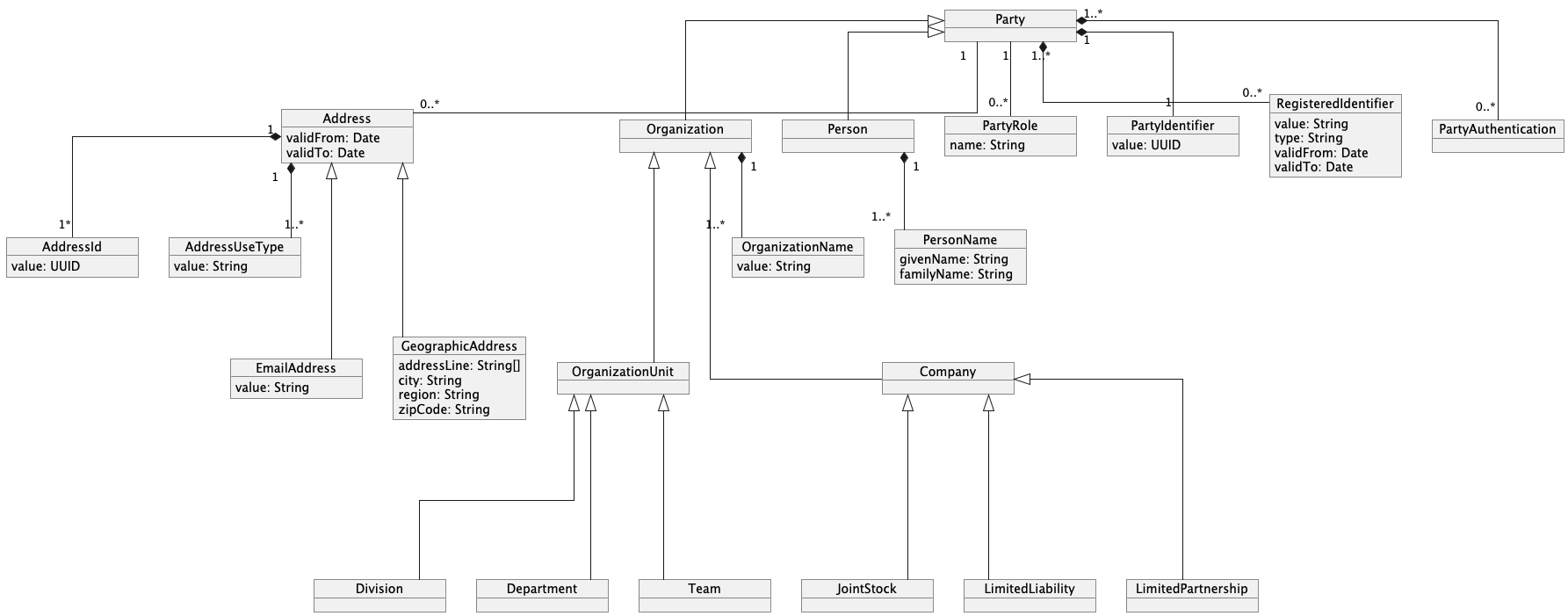

Now we can enrich it with all kinds of data necessary in our business, such as address or authentication data as well as behavior - like authentication strategies:

In this way, we can model any entity of any type, dynamically change its roles, and supplement it with policies and behaviors specific to the use case.

This is the archetypal Party model.

The Party archetype is a reusable business model used to represent different types of entities (individuals, companies, institutions) that play various roles, such as customer, supplier, user, partner, etc. Party allows for simplifying data management and relationships between these entities, avoiding issues of data duplication, logic redundancy within the model, providing high level of flexibility and reusability.

Features of the Party Archetype

Universal Representation of Parties - the Party archetype acts as a general, overarching representation of any type of party in the system, regardless of whether it’s an individual, a company, or another type of organization. In this way, a single Party model can handle data related to both individuals (e.g., first name, last name, residential address) and companies (business name, tax identification number, headquarters addresses).

Multiple Roles - each Party instance can take on various roles, such as Client, Supplier, Partner, or User. These roles can be assigned dynamically, allowing a single Party instance to fulfill different functions depending on the business context. Party archetype thus eliminates the need for separate classes for different entity types and allows more flexible role management.

Unified Data Model and Database - using Party facilitates storing information in a single, central data structure, helping to maintain consistency and avoid redundancy issues. This way, various applications and systems can refer to the same Party instance, simplifying synchronization and data maintenance.

Avoiding Data Duplication - Party reduces the need for duplicating data, such as addresses, phone numbers, or other shared attributes. Instead of recreating these fields in various classes, Party stores common data that is accessible regardless of the roles played by a particular instance.

Scalability and Flexibility - the Party model is easy to expand, as new roles and relationships can be added without needing to modify the core structure. Party is well-suited to scale with growing organizational needs, as it allows adding new functionalities and behaviors with minimal disruption to the existing model.

How it works?

Party

Party, as a central part of the model, aggregates data and functions common to all types of parties. It includes the management of roles, registered identifiers, and is capable of handling other types of metadata.

public sealed abstract class Party permits Organization, Person {

private final PartyId partyId;

private final Set<Role> roles;

private final Set<RegisteredIdentifier> registeredIdentifiers;

private final List<PartyRelatedEvent> events = new LinkedList<>();

private final Version version;

Party(PartyId partyId, Set<Role> roles, Set<RegisteredIdentifier> registeredIdentifiers, Version version) {

checkArgument(partyId != null, "Party Id cannot be null");

checkArgument(roles != null, "Roles cannot be null");

checkArgument(registeredIdentifiers != null, "Registered identifiers cannot be null");

checkArgument(version != null, "Version cannot be null");

this.partyId = partyId;

this.roles = new HashSet<>(roles);

this.registeredIdentifiers = new HashSet<>(registeredIdentifiers);

this.version = version;

}

public Result<RoleAdditionFailed, Party> add(Role role) {

//...

}

Result<RoleRemovalFailed, Party> remove(Role role) {

//...

}

public Result<RegisteredIdentifierAdditionFailed, Party> add(RegisteredIdentifier identifier) {

//...

}

public Result<RegisteredIdentifierRemovalFailed, Party> remove(RegisteredIdentifier identifier) {

//...

}

//...

}

Each specific type of party has to extend the base class. It gives us the ability to extend these types with additional metadata (like personal data) and appropriate behavior. We can present a Person as an example.

public final class Person extends Party {

private PersonalData personalData;

Person(PartyId id, PersonalData personalData, Set<Role> roles, Set<RegisteredIdentifier> registeredIdentifiers, Version version) {

super(id, roles, registeredIdentifiers, version);

checkArgument(personalData != null, "Personal data cannot be null");

this.personalData = personalData;

}

public Result<PersonalDataUpdateFailed, Person> update(PersonalData personalData) {

if (!this.personalData.equals(personalData)) {

this.personalData = personalData;

register(new PersonalDataUpdated(id().asString(), personalData.firstName(), personalData.lastName()));

} else {

register(PersonalDataUpdateSkipped.dueToNoChangeIdentifiedFor(id().asString(), personalData.firstName(), personalData.lastName()));

}

return Result.success(this);

}

//...

}

Parties are managed by PartiesFacade that is a service providing CRUD-like operations for registering parties of different types and manipulating their metadata.

class PartiesFacade {

//...

Result<PartyRelatedFailureEvent, Person> registerPersonFor(PersonalData personalData, Set<Role> roles, Set<RegisteredIdentifier> registeredIdentifiers) {

//...

}

Result<PartyRelatedFailureEvent, Company> registerCompanyFor(OrganizationName organizationName, Set<Role> roles, Set<RegisteredIdentifier> registeredIdentifiers) {

//...

}

Result<PartyRelatedFailureEvent, OrganizationUnit> registerOrganizationUnitFor(OrganizationName organizationName, Set<Role> roles, Set<RegisteredIdentifier> registeredIdentifiers) {

//...

}

Result<PartyRelatedFailureEvent, Party> add(PartyId partyId, Role role) {

//...

}

Result<PartyRelatedFailureEvent, Party> remove(PartyId partyId, Role role) {

//...

}

Result<PartyRelatedFailureEvent, Party> add(PartyId partyId, RegisteredIdentifier identifier) {

//...

}

Result<PartyRelatedFailureEvent, Party> remove(PartyId partyId, RegisteredIdentifier identifier) {

//...

}

Result<PartyRelatedFailureEvent, Person> update(PartyId partyId, PersonalData personalData) {

//...

}

Result<PartyRelatedFailureEvent, Organization> update(PartyId partyId, OrganizationName organizationName) {

//...

}

}

PartyId

PartyId might look trivial, but it is critical to understand the decision behind using an identifier that is unique throughout all supported party types.

Companies tend to use semantic keys as identifiers. For example:

- tax number or personal identification number (in Poland we call it PESEL) - although it is a unique identifier, it limits the flexibility of the model, because a company has no personal identification number and person is not obliged to know and use its tax number. It means you can use the identifier only in certain subset of your business

- phone number - the problem with phone numbers is that their pool is limited, and numbers are reused. When your contract with telecommunication service provider expires, your number can be sold to some other person or a company. It means you cannot rely on phone numbers long term.

- email address - not every business requires email to be verified, especially when you call the sales department to get a new insurance offer. The offer might be generated for your name, but sent to your wife's email address.

To avoid confusion, and ensure flexibility and functional scalability of the model, we should use a unique identifier. In terms of implementation PartyId is a record.

PartyId is an identifier of every party regardless its type. There is no such thing as OrganizationId or PersonId, because most things related to the Party archetype are type-agnostic (relationships, roles). Also, it is often the case that a party is sole trader, meaning it is both person and organization.

How do I generate PartyId?

PartyId like most identifiers can be generated either by the app or by the database engine. We recommend choosing the former as you have more control over it. The control include the possibility to unit-test it, or change its semantics.

RegisteredIdentifier

Beyond the need for unique identification of parties, which we addressed with PartyId, there is often a requirement to identify parties using semantic values such as tax numbers, personal identification numbers, passport numbers, or identity card numbers. As noted previously in the section on PartyId, these identifiers may not be unique and may not apply to all types of parties. However, addressing this need allows us to enrich the Party model with additional types of identifiers and to implement policies or rules that govern their use. Each party can have zero or more associated registered identifiers.

We modeled this using the RegisteredIdentifier interface.

public interface RegisteredIdentifier {

String type();

String asString();

}

Objects whose classes implement this interface are aggregated into a collection and managed within Party object.

public sealed abstract class Party permits Organization, Person {

private final PartyId partyId;

private final Set<RegisteredIdentifier> registeredIdentifiers;

//...

public Result<RegisteredIdentifierAdditionFailed, Party> add(RegisteredIdentifier identifier) {

checkNotNull(identifier, "Registered identifier cannot be null");

if (!registeredIdentifiers.contains(identifier)) {

registeredIdentifiers.add(identifier);

events.add(new RegisteredIdentifierAdded(partyId.asString(), identifier.type(), identifier.asString()));

} else {

//for idempotency

events.add(RegisteredIdentifierAdditionSkipped.dueToDataDuplicationFor(partyId.asString(), identifier.type(), identifier.asString()));

}

return Result.success(this);

}

public Result<RegisteredIdentifierRemovalFailed, Party> remove(RegisteredIdentifier identifier) {

checkNotNull(identifier, "Registered identifier cannot be null");

if (registeredIdentifiers.contains(identifier)) {

registeredIdentifiers.remove(identifier);

events.add(new RegisteredIdentifierRemoved(partyId.asString(), identifier.type(), identifier.asString()));

} else {

//for idempotency

events.add(RegisteredIdentifierRemovalSkipped.dueToMissingIdentifierFor(partyId.asString(), identifier.type(), identifier.asString()));

}

return Result.success(this);

}

//...

}

Similar to the Addresses described in the documentation, we also prioritize idempotency in this model. This means that repeatedly adding or removing the same identifiers will not cause errors, and the events returned as a result of such processing will either indicate a successful operation or its omission. However, only events that signal an actual change in the system's state are publishable, namely RegisteredIdentifierAdded and RegisteredIdentifierRemoved.

We have included a sample implementation of the identifier in the class PersonalIdentificationNumber.

Roles

A role archetype is intended to represent both the general role a given party might have, regardless of the specific use case, and the role it may play in its relationships with other parties. Here, we focus on the former.

A role is a simple value object containing the name (or type) of the role. Roles can be added or removed in an idempotent manner. A specific role may be represented either by an instance of the Role type with a specific name (e.g., "Customer") or through inheritance by creating subtypes. Each party can have zero or more associated roles.

Defining roles for a given party can be further refined with policies or rules that restrict the assignment of certain roles (e.g., roles specific to organizations cannot be assigned to individuals).

Roles are aggregated into a collection and managed within Party object.

public sealed abstract class Party permits Organization, Person {

private final PartyId partyId;

private final Set<Role> roles;

//...

public Result<RoleAdditionFailed, Party> add(Role role) {

checkNotNull(role, "Role cannot be null");

if (!roles.contains(role)) {

roles.add(role);

events.add(new RoleAdded(partyId.asString(), role.asString()));

} else {

//for idempotency

events.add(RoleAdditionSkipped.dueToDuplicationFor(partyId.asString(), role.asString()));

}

return Result.success(this);

}

Result<RoleRemovalFailed, Party> remove(Role role) {

checkNotNull(role, "Role cannot be null");

if (roles.contains(role)) {

roles.remove(role);

events.add(new RoleRemoved(partyId.asString(), role.asString()));

} else {

//for idempotency

events.add(RoleRemovalSkipped.dueToMissingRoleFor(partyId.asString(), role.asString()));

}

return Result.success(this);

}

//...

}

Addresses

In order to contact a party we usually need to store its addresses. Each party can have zero or more addresses. Each address can have one or more specific address uses such as contact address, billing address, invoice address, etc. We can distinguish a couple of types of addresses as well, including geographic address, web page address, email address, telecommunnication address (phone number).

We represent an address as an abstract concept – an interface. Each type of address will differ in structure and application. Every address may have its own lifecycle: after creation, it can be modified multiple times or eventually deleted. Potentially, the model can also be extended with functions for activation, verification, or blocking of the address. For these reasons, each address is uniquely identifiable through an AddressId.

public sealed interface Address extends AddressLifecycle permits GeoAddress {

AddressId id();

PartyId partyId();

Set<AddressUseType> useTypes();

AddressDetails addressDetails();

}

interface AddressLifecycle {

AddressUpdateSucceeded toAddressUpdateSucceededEvent();

AddressDefinitionSucceeded toAddressDefinitionSucceededEvent();

AddressRemovalSucceeded toAddressRemovalSucceededEvent();

}

The Geographic address is one of the most commonly used ones. It represents a geographic location at which particular party might be contacted.

public final class GeoAddress implements Address {

private final AddressId id;

private final PartyId partyId;

private final GeoAddressDetails geoAddressDetails;

private final Set<AddressUseType> useTypes;

//...

public record GeoAddressDetails(String name, String street, String building,

String flat, String city, ZipCode zip, Locale locale) implements AddressDetails {

static GeoAddressDetails from(String name, String street, String building, String flat, String city, ZipCode zip, Locale locale) {

return new GeoAddressDetails(name, street, building, flat, city, zip, locale);

}

}

}

Our experience shows that there are usually rules governing addresses, such as "each party can have exactly one active contact address." Rules and policies may also pertain to the type of entity, e.g., "only companies, not individuals, can have a billing address," or "a party may modify an address no more than once per quarter." These considerations led us to model addresses as a uniquely identifiable collection, which we modify atomically. This means that the critical section is built around all addresses, not each address individually. The group of addresses is also uniquely identifiable—this time, we can use the PartyId identifier for this purpose. Policies can be defined for any action as needed. An example we proposed is the AddressDefiningPolicy, which allows rules to be checked during address definition.

public class Addresses {

private static final AddressDefiningPolicy DEFAULT_ADDRESS_DEFINING_POLICY = new AlwaysAllowAddressDefiningPolicy();

private final PartyId partyId;

private final Map<AddressId, Address> addresses;

private final List<AddressRelatedEvent> events = new LinkedList<>();

private final Version version;

private final AddressDefiningPolicy addressDefiningPolicy;

private Addresses(PartyId partyId, Set<Address> addresses, Version version, AddressDefiningPolicy addressDefiningPolicy) {

this.partyId = partyId;

this.addresses = mapFrom(addresses);

this.version = version;

this.addressDefiningPolicy = addressDefiningPolicy;

}

public static Addresses emptyAddressesFor(PartyId partyId) {

return emptyAddressesFor(partyId, DEFAULT_ADDRESS_DEFINING_POLICY);

}

public static Addresses emptyAddressesFor(PartyId partyId, AddressDefiningPolicy addressDefiningPolicy) {

return new Addresses(partyId, Set.of(), Version.initial(), addressDefiningPolicy);

}

public Result<AddressDefinitionFailed, Addresses> addOrUpdate(Address address) {

if (addresses.containsKey(address.id())) {

return updateWithDataFrom(addresses.get(address.id()), address);

} else if (addressDefiningPolicy.isAddressDefinitionAllowedFor(this, address)) {

addresses.put(address.id(), address);

events.add(address.toAddressDefinitionSucceededEvent());

return Result.success(this);

} else {

return Result.failure(AddressAdditionFailed.dueToPolicyNotMetFor(address.id().asString(), address.partyId().asString()));

}

}

public Result<AddressRemovalFailed, Addresses> removeAddressWith(AddressId addressId) {

Optional<Address> address = Optional.ofNullable(addresses.get(addressId));

address.ifPresentOrElse(it -> {

addresses.remove(addressId);

events.add(it.toAddressRemovalSucceededEvent());

},

() -> events.add(AddressRemovalSkipped.dueToAddressNotFoundFor(addressId.asString(), partyId.asString())));

return Result.success(this);

}

private Result<AddressDefinitionFailed, Addresses> updateWithDataFrom(Address addressToBeUpdated, Address newAddress) {

if (addressToBeUpdated.getClass().isAssignableFrom(newAddress.getClass())) {

if (!addressToBeUpdated.equals(newAddress)) {

this.addresses.put(newAddress.id(), newAddress);

this.events.add(newAddress.toAddressUpdateSucceededEvent());

} else {

this.events.add(addressUpdateSkippedDueToNoChangesIdentifiedFor(addressToBeUpdated));

}

return Result.success(this);

} else {

return Result.failure(AddressUpdateFailed.dueToNotMatchingAddressType());

}

}

List<PublishedEvent> publishedEvents() {

return events.stream().filter(PublishedEvent.class::isInstance).map(PublishedEvent.class::cast).collect(Collectors.toList());

}

//...

}

Despite the connection between Addresses and Party, we have observed that their management (i.e., creation, updates, deletion) usually exhibits a different dynamic compared to operations such as authentication or role definition. Immediate consistency rules typically concern either authentication-related aspects or address-related matters. Rarely do we encounter rules that tie these areas together and require atomicity. Therefore, we decided to model Party and Addresses as separate aggregates. This opens up a potential opportunity to create a dedicated module for managing the address book, and consequently, perhaps even a microservice.

The model provides multiple events that inform us about the outcomes of executing specific actions, such as adding an address, updating it, or deleting it. The model ensures idempotency of operations. This means that multiple updates to an address with the same data, or repeated attempts to add or delete it, will not result in errors—the model interprets such situations as valid. This approach simplifies the model's usage by the infrastructure layer (such as REST controllers), which will not need to handle error mapping to response codes on its own.

To ensure that the model protects the address collection from violating consistency rules, access to it will be secured via the AddressesRepository interface.

interface AddressesRepository {

Optional<Addresses> findFor(PartyId partyId);

void save(Addresses addresses);

}

The functions described above, namely interaction with the address collection model, the repository, and event distribution, are orchestrated within the AddressesFacade, which serves as the entry point to the model.

Authentication

TBD

Party relationship

Problem statement

The previous model primarily focused on how to collect and structure information about individuals and organizations. Most of the model's behavior revolves around CRUD operations (Create, Read, Update, Delete). Within these operations, we identified areas where policies could be added (depending on requirements) and even where complex business processes, such as registration, could be built.

In reality, modeling parties as standalone entities is rarely sufficient. Typically, parties stored in a system are interconnected through various relationships, and reflecting these relationships is crucial to effectively manage and support complex business processes. In many systems, modeling parties as standalone entities falls short of capturing the complexity of real-world interactions. Relationships between parties are not merely connections; they carry rich semantics and play a critical role in business logic, authorization, and compliance. Without a robust mechanism for managing these relationships, organizations face several challenges.

Level 1 - semantic meaning of relationships

Every relationship must have a clear meaning. For instance, is the connection between two parties that of a "Supplier-Customer," "Employer-Employee," or "Parent-Child"? Misinterpreting or failing to define these semantics leads to confusion and unreliable system behavior. In a healthcare system for example, a "Doctor-Patient" relationship is distinct from a "Doctor-Consultant" relationship. The former involves direct care and medical decisions, while the latter might involve second opinions or advisory roles. Failing to distinguish these relationships could result in errors, such as granting the wrong party access to sensitive patient data.

Level 2 - symmetry vs asymmetry

Party relationships can be symmetric (mutual) or asymmetric (directional). While symmetric relationships are simpler, asymmetric ones are more concrete, as they require explicit role definitions and directionality.

Symmetry implies mutuality, requiring consistent status for both parties. For example, in a "Friend-Friend" relationship, the system must ensure reciprocity, such as reflecting changes like blocking or removing correctly for both sides. Symmetric relationships are more abstract and less specific, which can limit their usefulness in scenarios where distinct roles or responsibilities are critical.

Asymmetric relationships on the other hand need distinct roles and clear directionality. For example, in a "Manager-Subordinate" relationship, the system must define the manager's authority and scope (e.g., teams, projects).

In reality, most relationships are asymmetric, where each party plays a distinct role. For example, a person may be a "Manager" in one relationship and a "Subordinate" in another. Capturing and managing these roles accurately is essential for proper functionality.

Level 3 - roles in relationships

One critical aspect of relationship modeling is that a party can take on different roles depending on the context of each relationship. This flexibility reflects real-world scenarios where individuals or organizations often operate in varying capacities across multiple interactions.

In a corporate setting, an employee might be:

- A "Manager" in a relationship with their subordinates.

- A "Team Member" in a project-based team relationship.

- A "Mentor" in a mentorship program.

In an organizational context, a company might simultaneously be:

- A "Supplier" to one business partner.

- A "Customer" to another.

- A "Partner" in a strategic alliance.

It is important to capture these roles to gain the ability to assign specific roles ensures that the system accurately represents the responsibilities, permissions, and expectations associated with each relationship. Different roles may also have different levels of authority or access within the system. For instance, a "Manager" may have permission to approve tasks, while a "Team Member" may only view or execute them. Modeling roles dynamically allows for scenarios where the same party operates in multiple capacities without redundancy or conflict.

If roles are not clearly tied to specific relationships, the system risks applying incorrect permissions or responsibilities universally to a party, which can lead to errors in workflows, compliance issues, or security breaches. By allowing parties to take on different roles in different relationships, the system can better reflect real-world complexities and support nuanced business processes.

Level 4 - on-behalf-of scenarios

Relationships often involve acting on behalf of another party. For example, in the e-mobility domain, a Charging Point Operator can log into the system on behalf of the station owner (Local Charge Provider) to assist with configuring the station. This approach ensures that the CPO has exactly the same view and capabilities as the station owner, making it much easier to manage access rights and permissions. This type of delegation requires precise modeling of roles and permissions.

Level 5 - type constraints on relationships

Some relationships may need to be restricted based on the type of party. For example, only organizations may be suppliers, as a business policy prohibits contracting with individuals as vendors. For example, in a procurement system, a rule might enforce that "Supplier-Customer" relationships can only exist between companies, rejecting any attempt to register an individual as a supplier. Without this restriction, contracts could be improperly established, leading to compliance or legal issues.

Level 6 - enforcement of business rules

Business rules play a critical role in defining and restricting the nature and scope of party relationships. By enforcing these rules, systems can ensure compliance with organizational policies, maintain operational efficiency, and support scalability. Modeling these constraints effectively can be challenging but is necessary for real-world scenarios. Business rules might relate to:

- Quantitative Constraints - Rules that limit the number of specific relationships a party can have. For example, a company may enforce a rule that it can have no more than 10 active suppliers at any given time, ensuring manageability and focus on strategic partnerships. In an HR system, a manager might be restricted to supervising no more than 12 direct reports to maintain a practical workload and oversight capacity.

- Qualitative Constraints - Rules that define which types of parties can engage in specific relationships. For example, an organization might prohibit individuals from being suppliers, restricting this role to registered businesses. This ensures compliance with legal and procurement policies.

- Temporal Rules - Constraints based on the time period of the relationship. A contract might stipulate that a supplier relationship cannot be terminated before a 6-month minimum term or seasonal employees can only have an active relationship during specific months.

What's next?

The above demonstrates that managing relationships among users, clients, partners, and various types of entities can be a very complex issue, where entities can assume multiple roles across multiple relationships forming big graphs of interconnections.

Possible solutions

While searching for the appropriate model, we identified key questions that will serve as our architectural drivers:

- Do we need to ensure immediate consistency of the business rules concerning relationships? Is ensuring immediate consistency even feasible? What would be the consequences of relaxing consistency?

- Should any changes to a Party affect its relationships? For example: can we add relationships to a Party that has been blocked?

- Should any changes in relationships affect a Party? For instance: can we deactivate a Party that serves as a "Manager" for 10 subordinates, or must I first dissolve those relationships?

- How should relationships be stored? Should they be part of the Party model or constitute a separate entity, similar to addresses?

Additionally, we must remember the two dimensions of the model. Relationships allow us not only to manage the rules of associations between parties (i.e., who can establish a relationship with whom, what types of relationships are permissible, and how many such relationships are possible) but also to answer key questions from the perspective of business process rules (e.g., what is the workload of a manager, which partner company operates in Warsaw and can repair faucets) and authorization (e.g., what role a person plays in relation to a specific company or who is the payer for a given customer's orders).

Analysis

In terms of consistency we might distinguish two types of business rules - immediately consistent, and eventually consistent. Let's consider following set of constraints:

- quantitative constraint, like "a manager can have no more than 10 subordinates"

- qualitative constraint, like _"MANAGER OF relationship can be only assigned between persons with employee role"

We could keep outgoing relations within Party model:

import com.softwarearchetypes.party.PartyRelationship;

class Party {

private final PartyId partyId;

private Set<PartyRelationship> relationships;

void addRelationship(PartyRelationship partyRelationship) {

relationships.add(partyRelationship);

}

//...

}

class PartyFacade {

//...

void addRelationship(PartyId fromId, Role fromPartyRole, PartyId toId, Role toPartyRole, RelationshipName name) {

Party fromParty = partyRepository.findBy(fromId); //with all relationships

Party toParty = partyRepository.findBy(fromId); //with all relationships

if (canCreateRelationshipFor(fromParty, fromPartyRole, toParty, toPartyRole, relationshipName)) {

fromParty.addRelationship(new PartyRelationship(fromId, fromPartyRole, toId, toPartyRole, relationshipName));

}

partyRepository.save(fromParty);

}

//...

}

In this case:

- All relationships are directly available within the

Partymodel, making it easier to retrieve, manage, and update them in one place. Fetching all relationships for a given party requires a single query or operation. - Relationships are inherently tied to the party they belong to, aligning closely with the domain model.

For example, a "Customer" entity naturally holds all its relationships, such as purchases, suppliers, or representatives. - For smaller datasets or systems with limited relationships, embedding relationships directly simplifies the architecture and avoids the need for a separate relationship table.

- Operations focused on a single party’s relationships (e.g., viewing a customer’s suppliers) might be faster, as data is already localized within the Party model.

- Keeping relationships tied to a party ensures context is preserved and reduces the risk of orphaned or unrelated relationships.

- Embedding relationships in the

Partymodel eliminates the need for additional infrastructure, such as separate tables or services, simplifying the initial development process.

On the other hand, we might identify following issues:

- For quantitative constraints large numbers of relationships can overload the Party model, leading to performance degradation and inefficiency in handling high-volume entities.

- The Party model becomes a "God Object," tightly coupled with relationship logic, making it harder to maintain and evolve.

- Retrieving or filtering relationships can become slow and resource-intensive, especially for complex queries or large datasets.

- Combining entity data and relationship management in one model reduces separation of concerns, complicating testing, maintenance, and integration.

- For qualitative constraints (concerning roles, types, existing relationships for both upstream and downstream party), enforcing business rules or extending the relationship model for new scenarios becomes harder when all logic is embedded in the

Partymodel. - The centralized object model is supposed to support atomicity (especially in case of concurrent access). Qualitative constraints that are based on the details of the other side of relationship might need the second object to be locked), which might effectively degrade system's availability.

We may conclude that this option would work well for:

- Systems with a small or manageable number of relationships.

- Scenarios where the primary focus is on individual parties and their direct connections.

- Environments where simplicity and fast development outweigh concerns about scalability or modularity.

Solution

The bigger the scale gets, the less manageable and scalable the model becomes. Is it possible, then, to loosen the consistency requirements? To answer this question, we should ask what would be the consequences of keeping relationships separately? What would happen if a manager have 11 subordinates assigned? What would happen if "manager of" relation is incorrectly assigned to a non-employee (because an employee became a partner "in the meantime")? Maybe these situations are rare enough that breaking the business rule has very little impact and is acceptable. Maybe asynchronous reconciliation would do the job. Our experience shows that scalability, flexibility and availability are usually way more important than strong consistency, especially, when managing party metadata and relations are processes that are separated in time by design.

This is why we propose the following solution.

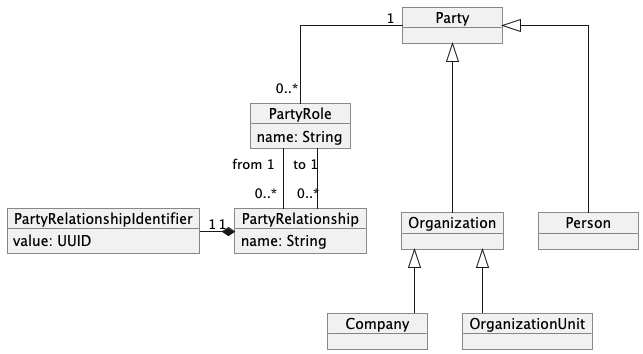

The Party relationship archetype complements the Party archetype, providing a model to represent different types of relationships between entities.

Features of the Party Relationship Archetype

Role-Based Relationships supporting symmetry and asymmetry - the Party Relationship Archetype distinct roles for each party in a relationship, enabling modeling of asymmetric interactions (e.g., "Manager-Employee" or "Supplier-Customer"). It is possible to have both mutual (e.g., "Friend-Friend") and directional relationships (e.g., "Parent-Child"), offering flexibility to represent real-world scenarios.

Temporal Context - the archetype allows relationships to include start and end dates, supporting the management of active, expired, and historical relationships.

Scalability - the solution accommodates complex networks of relationships with potentially large datasets, enabling scalability for hierarchical, many-to-many, and multi-party scenarios.

Dynamic and Flexible Typing - it supports a wide variety of relationship types, with the ability to extend and adapt to evolving business needs without significant structural changes.

Policy and Rule Enforcement - the Party Relationship Archetype integrates business rules and constraints, such as restricting certain relationship types or limiting the number of active relationships for a given party. Rules can be implemented via policies (aka strategy patern) or via integration with rule engine.

Delegation and Representation - the model supports cases, such as identifying a user’s role within the system or determining which entities they are associated with, particularly for authentication or access control, and for "on-behalf-of" scenarios.

How it works?

Party Relationship

Although the problem of managing party relationships is complex, the model of the relationships themselves is straightforward.

public record PartyRelationship(PartyRelationshipId id, PartyRole from, PartyRole to, RelationshipName name) {

//...

}

It is a simple record that holds information about party IDs, their roles, and the relationship name, and is uniquely identifiable. This design allows relationships to be managed independently of parties, addressing the issues identified in the analysis.

The logic behind creating/removing relations is defined in PartyRelationshipsFacade

public class PartyRelationshipsFacade {

//...

public Result<PartyRelationshipDefinitionFailed, PartyRelationship> assign(PartyId fromId, Role fromRole, PartyId toId, Role toRole, RelationshipName name) {

//...

}

public Result<PartyRelationshipDefinitionFailed, PartyRelationshipId> remove(PartyRelationshipId partyRelationshipId) {

//...

}

}

Party Role

Like we have already mentioned, a role archetype is intended to represent both the general role a given party might have, regardless of the specific use case, and the role it may play in its relationships with other parties. Here, we focus on the latter.

A party role is a simple value object containing the name (or type) of the role and the identifier of a party it is assigned to. The reason for holding the party identifier is to enable party relationship to connect role with particular side of the relation.

Defining party roles might be further refined with policies or rules that restrict the assignment of certain roles (e.g., roles specific to organizations cannot be assigned to individuals). We implemented that by providing PartyRoleDefiningPolicy interface.

interface PartyRelationshipDefiningPolicy {

boolean canDefineFor(PartyRole from, PartyRole to, RelationshipName relationshipName);

}

The interface is used in PartyRoleFactory which is responsible for creating objects that align with the current rule set.

Further considerations

How to store parties and their relations?

The example in the code is based on an in-memory database that relies on hash tables. In reality, however, we should choose one of the available types of databases, such as relational, document-based, or graph databases.

Relational and document-based databases generally allow us to store our parties and their relationships in a similar way. In relational databases, we can either have a separate table for the parties and another table for the list of relationships (edges of the graph), or we can have a single table where a field for relationships stores all outgoing relationships from a given node in a JSON format.

Document databases, such as MongoDB, allow you to store data in flexible documents. A common approach is to store parties as individual documents in a collection, and either reference the relationships in separate documents (a collection for edges) or embed the relationship data directly within the party document. This approach offers flexibility and scalability but might become cumbersome with very complex relationships.

Alternatively, we can also use graph databases, such as Neo4j, which are purpose-built for managing relationships between entities. In a graph database, parties would be stored as nodes, and relationships between them would be stored as edges. This model is highly optimized for querying relationships and is especially effective when the relationships themselves are as important as the entities. By using graph databases, we can easily traverse relationships and query the graph structure without needing complex JOINs or relationships tables. This is a powerful solution for cases where relationship querying and pathfinding are core features of the application.

It's also important to note that the choice of a database does not mean that everything has to be stored within a single engine. There's nothing preventing us from writing data to a relational database (where it's easier to manage transactions and implement an outbox for emitting events), while using a graph database for more complex queries needed for building the read model.

How to use the potential?

Many of the functions of the Party and Party Relationship model is CRUD-like. We have pointed out that any of these functions might be enhanced with policies, integration with rule engine or simply become a business process on its own (like party registration or address change).

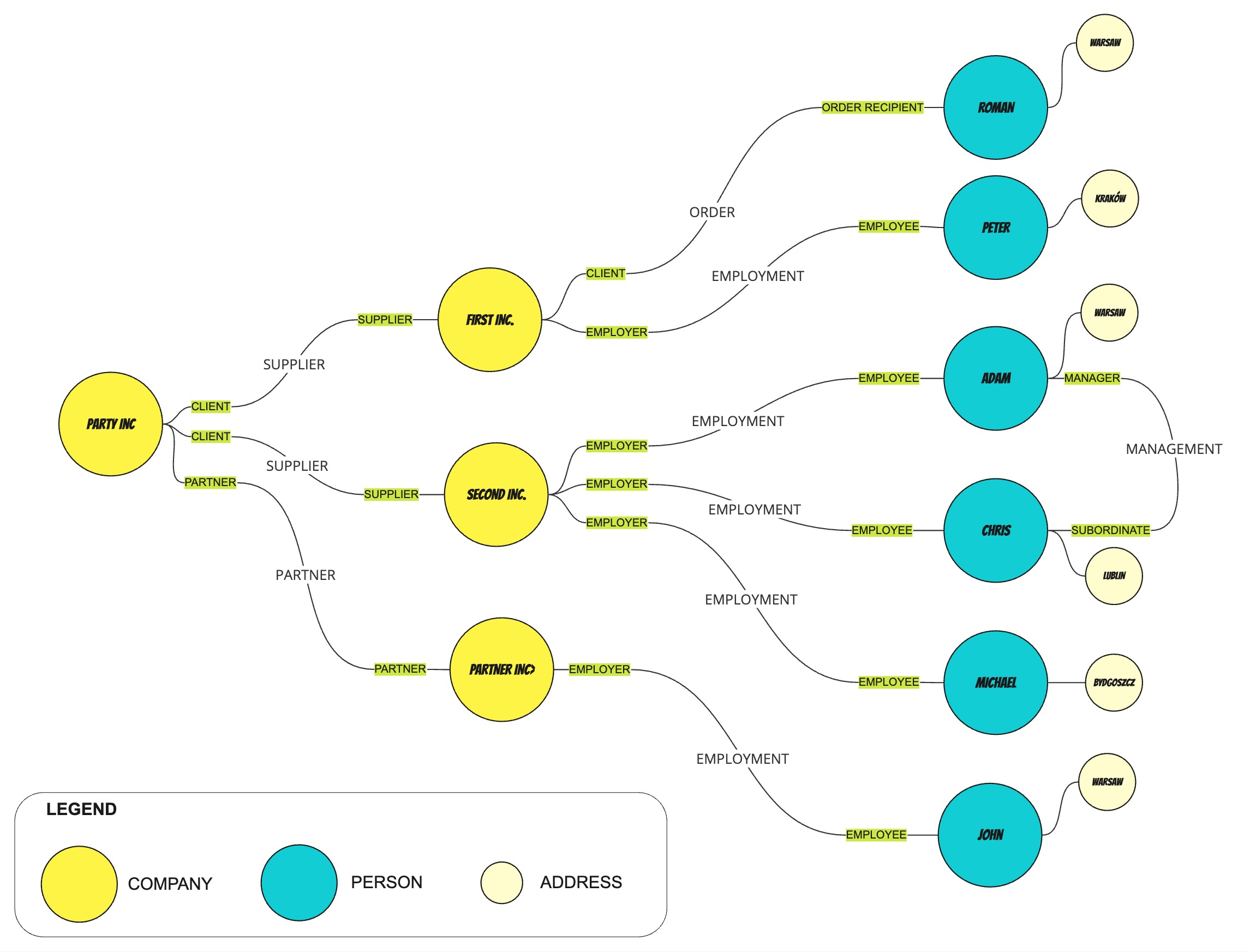

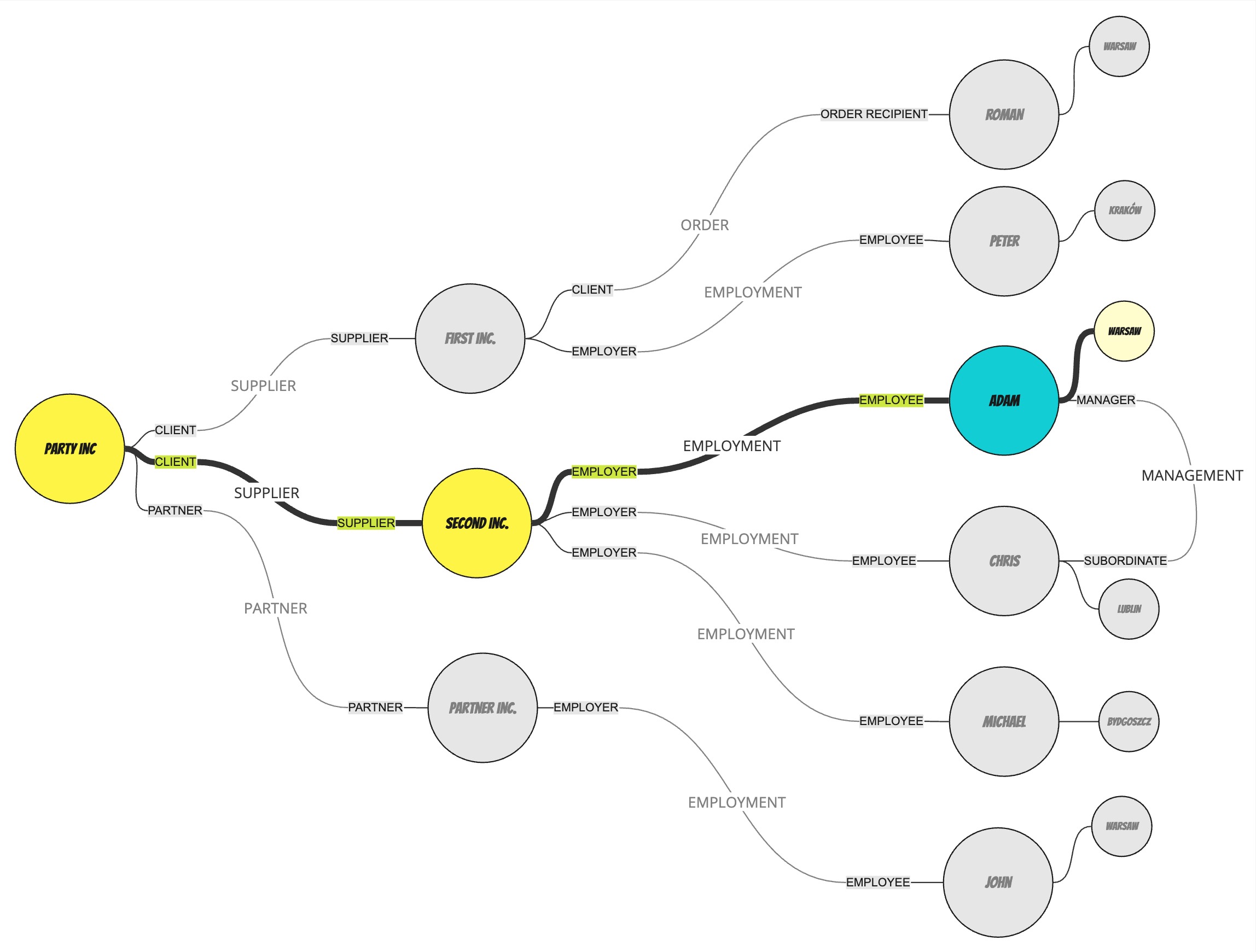

However, the potential is even bigger. Let's consider a following graph of parties.

Apart from finding particular by their identifiers or parties that are directly related with others we could create a query like this:

Find an employee of our supplier who operates in Warsaw

If we look at the graph we could manually find the path to the answer

Just to give you an example of how to approach automating such queries, we created a PartySearch class

public class PartySearch {

private final PartiesQueries partiesQueries;

private final PartyRelationshipsQueries partyRelationshipsQueries;

private final AddressesQueries addressesQueries;

PartySearch(PartiesQueries partiesQueries, PartyRelationshipsQueries partyRelationshipsQueries, AddressesQueries addressesQueries) {

this.partiesQueries = partiesQueries;

this.partyRelationshipsQueries = partyRelationshipsQueries;

this.addressesQueries = addressesQueries;

}

//sample query - here is the place where we could apply graph database queries

List<Party> findMatching(Search search) {

List<Party> result = new LinkedList<>();

if (search.partyPredicate != null) {

result = partiesQueries.findMatching(search.partyPredicate);

}

if (search.partyRelationshipPredicate != null) {

if (!result.isEmpty()) {

List<PartyId> foundIds = result.stream().map(Party::id).toList();

List<PartyId> toPartyIds = partyRelationshipsQueries

.findMatching(it -> foundIds.contains(it.from().partyId()) && search.partyRelationshipPredicate.test(it))

.stream()

.map(rel -> rel.to().partyId())

.toList();

result = partiesQueries.findMatching(it -> toPartyIds.contains(it.id()));

}

}

if (search.addressPredicate != null) {

if (!result.isEmpty()) {

result = result.stream().filter(party -> !addressesQueries.findMatching(party.id(), search.addressPredicate).isEmpty()).collect(toList());

}

}

return result;

}

}

This is a very simple query that utilizes a set of predicated, defined in a Search object

record Search(Predicate<Party> partyPredicate,

Predicate<PartyRelationship> partyRelationshipPredicate,

Predicate<Address> addressPredicate) {

}

We could develop the mechanism further bringing the specification pattern int play, joining predicates with logical operators like AND, OR, etc. However, these are the graph databases that are optimised for this kind of queries. That is why we see a huge potential there.

If we think of parties and their relations as graphs, we can query the model in endless number of ways to answer questions important in other business processes.

Further improvements

Everything you've seen so far is only a glimpse of what the Party archetype can offer. Soon, we'll explore more about capabilities and assets.